This month Utah Foundation will release the fourth part of its report looking at generational differences among Utahns and their national counterparts. The first problem encountered when writing this report is defining the generations themselves. Each organization has a different generational definitions, but the table below outlines some of the more common generations as well as a few alternatives.

Most Common Generations |

||

| Generation | Alternate Names | General Birth Cohort |

| Greatest Generation | GI Generation, Traditionalists | 1910-1928 |

| Silent Generation | Lucky Few | 1928-1945 |

| Baby Boomers | 1946-1964 | |

| Generation X | 1965-1980 | |

| Millennials | Generation Y, the Echo Boomers, Generation We and many others | 1881-1999 |

| Post-Millennials | Generation Z, , Homelanders, Generation We (yes, again), and others | 2000-2020 |

Alternative Generations |

||

| Oregon Trail Generation | Generation Catalano, Xinnials or The Lucky Ones | 1973-1987 |

| Generation 2020 | 1990-2009 | |

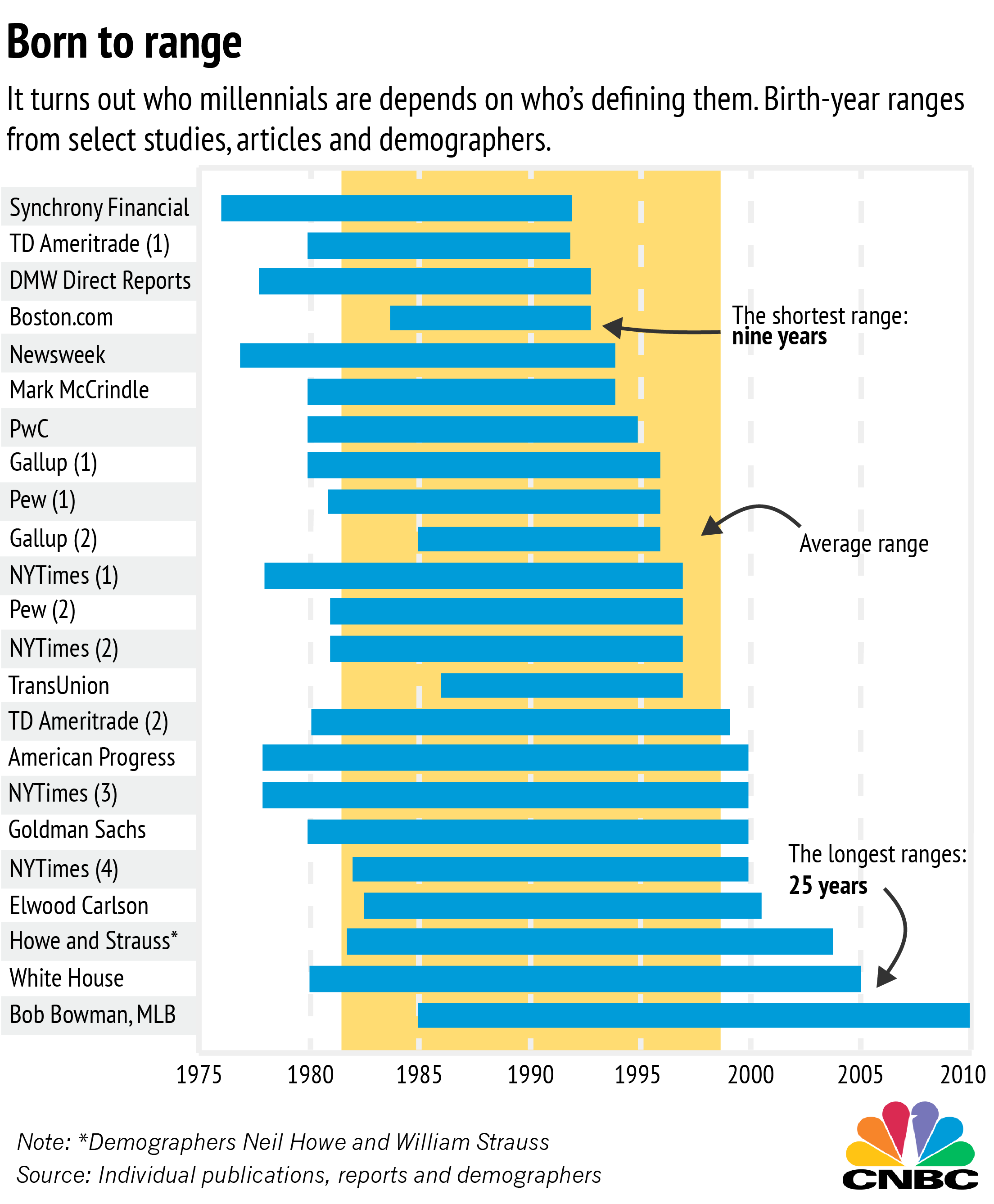

Essentially, there is a lot of dispute the name, place and birth cohort of generations. For example, CNBC shows Millennials have nearly 20 different age definitions. Some entities like the New York Times has even defined Millennials four different ways.

Utah Foundation wanted to compare national data to Utah in the generation’s report, with a focus on Pew Research Center surveys. Accordingly, we used Pews generational definitions, shown as Pew (2) in the CNBC figure.

During the execution of the study, the topic of generational definitions continually came up in discussion. One of the more interesting proposals was that while 20-year generations might have been sufficient in the past, the rapid change of technology has limited the group of individuals that can all have the same characteristics.

For example, a 34-year-old (a millennial by our definition) began college in 2000 and just purchased her own cell phone. Rather than Wikipedia, she had to rely on limited online resources, and actual books in the library. While she had just created her first email account, she still doubted its usefulness and all her social networks were built through face-to-face interactions.

Compare that to a 27-year-old who entered college 2006. While he owned a cell phone in high school, he only used it for phone calls. Research journals were available online for his papers and he only went to the library for group projects or a quiet place to study between classes. He chatted with his friends using MSN and was excited that he could join Facebook which was exclusively for college students.

Then there is the 18-year-old soon-to-be college freshman (also a millennial) who can’t remember a time without the internet. She is puzzled how she survived before she got her touchscreen cell phone with a data plan her first year of high school. There isn’t a trivia question she can’t answer within 5 seconds using Google, and she relies on YouTube and Netflix for all her entertainment. She chats with her close friends face-to-face through her cell phone using apps like Facetime and keeps track of all her other friends and families through their tweets and Facebook updates.

While Utah foundation classifies these three individuals as Millennials, is someone who didn’t own a cell phone until their adult life really all that similar to someone who goes over her 6GB dataplan every month? What would it look like instead if generational differences were be defined by technological advancement?

Ultimately generational definitions will probably depend on what it is exactly one is studying. Although it might seem overreaching to lay out characteristics that define an entire generation, a lot can be learned from it. Utah Foundation has highlighted a number of significant generational differences on an array of topics such as demographics, workplace preferences, housing, and politics

Categories: